It governs much of his virtual life in those days, yet the story of where he first materialized is deeper than he realizes.

You are surrounded through it.

You can’t send an email without touching it.

You can’t stream your favorite series without hosting it in your home.

He doesn’t know where he’s going, but he follows his every move and instructs him to turn left.

It’s “the cloud” and whether you realize it or not, it’s probably invaded your virtual life.

But what does “the cloud” do?

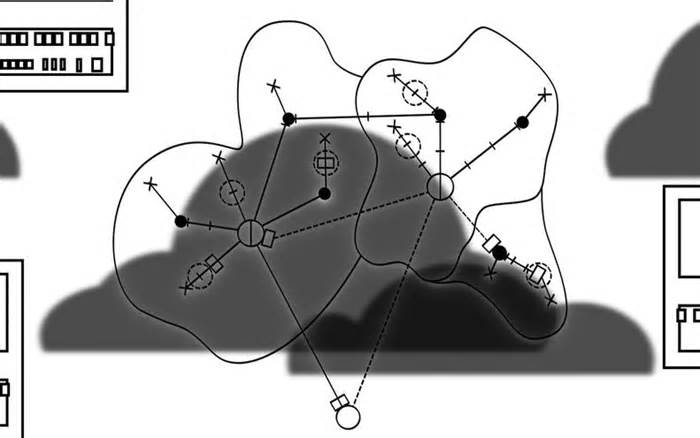

The cloud is a formula for millions of hard drives, PC servers, signal routers, and fiber optic cables.

These are, in a way, like water droplets, ice crystals, and aerosols that form a genuine cloud.

They are nebulous. They are changing. But they are very similar to each other in wonderful distances of area and time.

The genuine purpose of the cloud is undiced around us, silently, creating ever-present connectivity.

And just like a genuine cloud, it can bring benefits and dangers. The cloud makes installations more affordable and available to others around the world. It is helping corporations update their customers’ products and enables remote paintings across industries. how we can track behaviors on each and every online page we visit. This can put our virtual privacy in the hands of tech giants. And if the cloud failed, our growing, more commonly unconscious, dependence on it would painfully disappear. .

Why, let’s go back to the early days of the Cold War with the Soviet Union.

After the Soviets defeated the Americans in the area in 1957, the U. S. Department of Defense(USA I needed to work harder in studies and development. The following year, he formed the Advanced Research Projects Agency. This company would create the draft internet a decade. Later, it was called ARPANET and connected 4 university computers through telephone lines.

ARPANET is the result of a new and questionable view of computers defended through engineer and psychologist J. C. R. Licklider.

In 1962, Licklider, known as “Lick”, appointed head of the agency’s data processing generation office, and with his budget has put forward a vision of those machines very different from that of his peers.

Lick did not build new computers for each and every project, but sought to consolidate resources into a network of think tanks that Americans can access according to their needs. This vision, which has become the foundation of ARPANET and later the Internet, is the premise of cloud computing.

When you access knowledge on the Internet, you are actually requesting files from a server. The files are divided into small packets of information, which can be combined or take absolutely other paths to your device, where they are reassembled. a bit complicated, but all that literally is that you are connected to the network.

One of the first visual representations of a cloud dates back to 1971.

Last year, AT Telecommunications

It showed some cloud-like forms that would tie the hardware together, even though Dorros didn’t know which computers or phone lines would be combined at any given time.

By the early ’90s, engineers had become accustomed to referring to the Internet this way, but the concept of “cloud computing” became widespread in the 2000s. In March 2006, Amazon introduced its first cloud-based service as a component of its Amazon, or AWS, Internet services.

Initially, Amazon was only making plans to create a platform to help other companies create online stores, but it soon began to recognize that many of the equipment and databases it built could be useful outside of e-commerce.

Amazon began renting the server area and knowledge base equipment that allowed corporations to launch and maintain programs at a lower cost than starting from scratch. For example, Zillow, the online real estate website, uses AWS to buy a hundred terabytes of photographs and knowledge of the house. than to manage the mandatory servers themselves.

Using an external server can be more secure than managing yours, as it’s much less likely to overload, and many of those servers will back up your files. Calm, and many have knowledge centers around the world, which speeds up the loading of the site for foreign users.

The cloud can also give you more computing power than you can seamlessly get on your own, allowing you to successfully use a supercomputer from your smartphone.

Cloud installations are divided into 3 categories: software, platforms, and infrastructure.

Cloud-based software is just programs that run on the internet so users don’t have to download anything. This category is especially popular for widely used systems like the Slack instant messaging platform or the Dropbox record-sharing app.

Then, cloud platforms, such as Google’s App Engine, are virtual environments in which developers build to run them.

Finally, cloud infrastructure provides the server area that a visitor manages remotely.

Consolidating the global virtual on a few hard servers is incredibly effective. And the cloud gives us unprecedented connectivity. This is the basis of the “Internet of Things,” in which built-in sensors connect physical items such as agricultural cars or construction thermostats to the Internet. Once connected to the cloud, all those elements can act autonomously, running for us without human intervention.

But while the cloud can make our jobs more effective and our lives more flexible, we pay for one’s privileges with our knowledge and security. Every action we take online, we transmit non-public data to corporations looking to maximize profits. that may derive from us. Many internet sites and apps track our virtual movements and sell this knowledge to marketers. Cloud service providers can also collect knowledge from programs built on their servers. will be misused.

As we attach more of our daily lives to the cloud, we rely on a network that controls everything from the other people we meet on dating apps to how our credit cards work.

We also lose sight of the fragility of the system. The cloud only exists thanks to physical parts, such as fiber optic cables as thin as paper, that break and degrade smoothly over time. Hearing talk can take large portions of the connection, it’s hard not to wonder if we’ve made a bad deal.

Spektrum and scientific American staff

Michael Tabb, Jeffery DelViscio and Andrea Gawrylewski

Michael Tabb, Jeffery DelViscio and Andrea Gawrylewski

Spektrum and U. S. Clinical Staff

Michael Tabb, Jeffery DelViscio and Andrea Gawrylewski

Spektrum and scientific American staff

Spektrum and scientific American staff

Spektrum and scientific American staff

Discover the science that is turning the world. Explore our virtual archive up to 1845, articles through more than 150 Nobel laureates.

To follow

Arab American scientist

It supports science journalism.

Thanks for Scientific American. Knowledge waits.

Already a subscriber? Identify.

Thank you for Scientific American. Create your single account or log in to continue.

View subscription options

Keep with a Scientific American subscription.

You can cancel at any time.