Across the county, calls for police investment to be redirected to social services, which are more provided to respond to incidents of intellectual fitness, have increased in recent months.

Mental fitness incidents account for 10% of all police calls in the United States, according to a 2015 report through the Treatment Advocacy Center, a national nonprofit organization targeting the treatment of serious intellectual diseases. The same report found that adults with serious untreated intellectual diseases accounted for one in four fatal encounters with police and were 16 times more likely to be arrested by police than others.

These figures raised the question of whether it is more advantageous to assign incidents of intellectual fitness to police officers. One solution that has gained popularity are cell crisis reaction units, which provide other people in intellectual aptitude tests on site and professional workers.

But intellectual aptitude officials overseeing cell crisis reaction sets in Philadelphia’s domain said that “working together” with law enforcement is optimal, rather than separately. These associations can provide an additional layer for law enforcement and crisis officials when an intervention wears down, they said.

Work begins with educating and educating police departments about what others with intellectual fitness disorders face, said Shamit Chaki, director of the Crisis Response Center at Einstein Medical Center. The media runs on a cellular unit at the John F. Kennedy Center for Behavioral Health.

“There is no linear direction in handling a crisis,” said Chaki, who helped shape the Philadelphia Police Department. “We give the police equipment to other people and a repository of information that they can be inspired by. We need you to know that recovery is imaginable for others facing these crises.”

Scientific policy sent every Monday, Wednesday and Friday night to your inbox.

The first cellular crisis unit in the United States, Cahoots, which means Crisis Aid Helping on the Streets, was established in Eugene, Oregon, more than 3 decades ago. Since then, the good fortune of the unit has encouraged many others across the country, adding Philadelphia and Chester counties.

The cell crisis team overseen through the Philadelphia Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual Disabilities Services (DBHIDS) has maintained a “strong reciprocal partnership” with the city’s police department for decades, said DBHIDS Commissioner David T. Jones. The team responds to approximately 3,700 crises consistent with the year, Jones said, and provides an adequate reaction involving and stabilizing the caller, who can reach the city’s intellectual fitness line or be routed through the 911 dispatchers.

“If a caller says they are calling because they are lonely and isolated, our delegates contact them and inform them of the available facilities,” Jones said. “If the call is sharper and the individual expresses the concept of hurting himself or others, the delegate will keep them engaged and send them to the cell team. If they have a gun and say they intend to shoot themselves, the paintings would also involve the police. “

Jones is aware that the presence of police officers can worsen certain conditions, which is why the cell team is doing everything possible to respond to the appellant’s requests. It is not for the appellant to ask a qualified doctor or employee to be on site, he said.

The cell team “often acts as the first to respond,” he said. “If necessary, crisis officials will call the police. And if the police react to a scenario where the individual wants behavioral intervention, they call us.

While researchers warn of an unendible intellectual aptitude crisis due to COVID-19 (a recent report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that 11% of adults said they had seriously committed suicide by the end of June), the city’s cell crisis unit has changed to join with others in new tactics in FaceTime or Zoom Jones Said. In 2018, the branch incorporated 3 cell phones to respond to young people and adolescents.

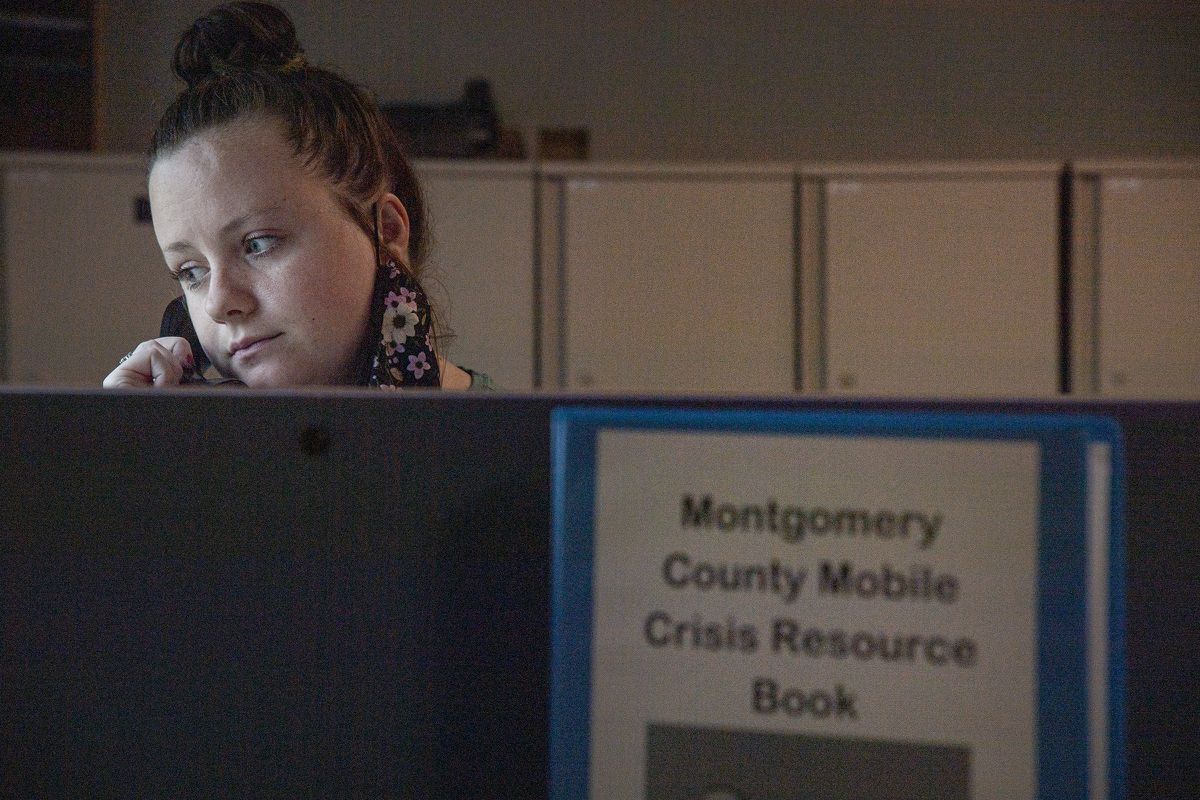

The Chester County Mobile Crisis Unit, overseen through Holcomb-Chimes Behavioral Health Systems since 2009, receives more than 2,500 calls according to the month, either directly or through 911 dispatchers, said Sonja Kenney, the unit’s clinic manager. The unit basically focuses on verbal descaling.

“We are made to take care of the maximum conditions without a police force,” he said. “Contacting the police would be the last resort, as if there was involuntary hospitalization or if there could be violence or danger.”

In the county, the crisis officer’s purpose is to make the caller “feel comfortable and have a concept of what would possibly have led him to call,” said Jess Fenchel, vice president of behavioral fitness at Access Services, who manages a cellular crisis. center serving the county and its surroundings.

“During the call, we have a concept of other people’s hopes and expectations,” Fenchel said. “It takes a little courage to call. Then we evaluate your security point and ensure some stability. We want to hurry, then slow down. We want to succeed in other people quickly, but then slow down a situation and they remain calm,” so they can make the most productive decisions.

Montgomery County created the Mobile Crisis Unit in 2013. The unit, which responds to calls from 911 dispatchers, has partnered with “almost every 50” county police departments.

Vera Zanders, deputy administrator of the County’s Office of Mental Health, Development of Intellectual Disorders and Early Intervention, said the reaction to cell crisis is one of the ultimate elements of a physically powerful intellectual aptitude formula in a community.

“It’s an essential way to invest cash if we need to help others recover,” Zanders said. “We need to relieve the police.”

In general, emergency reaction systems across the country are trained to respond to behavioral fitness crises, so over-reliance on first responders can position them in comfortable scenarios, Fenchel said.

Even when officials get intellectual aptitude training, “don’t liveArray … in this area on how to talk to a user on the most complicated day of their life,” said Anna Trout, director of seizures and detour at the county office. Mental fitness.

“This is a request from the police, but not a request from the cell crisis team,” Trout said. “It’s just not their role, and when it’s not someone’s role when the crisis is potentially life and death, why would we continue to place them on this scenario when we have other options?”

If you or know you are thinking of suicide, call the National Suicide Prevention Line at 1-800-273-8255 or send TALK to the Crisis Message Line at 741741.

Scientific policy sent every Monday, Wednesday and Friday night to your inbox.