Ten years ago, a Japanese designer named Ichiwo Sugino revamped its appearance. As retirement approaches, she will grow her hair out, mimicking the look of an artist she admires. His friends encouraged him to take his personal transformation further, so he took a roll of duct tape and rearranged his face. By posting the result on Instagram, she discovered a new calling.

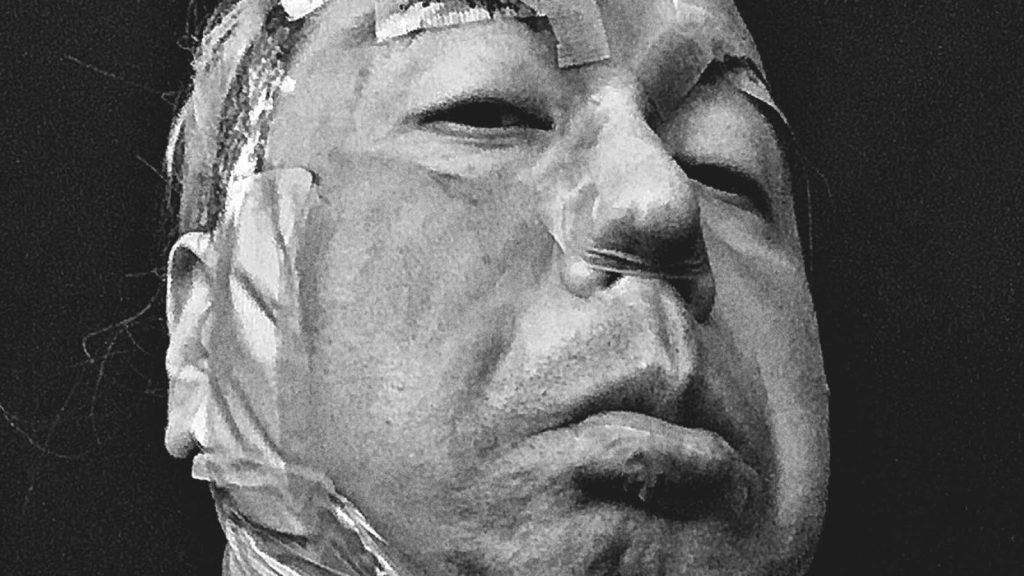

Sugino has since impersonated thousands of people, ranging from Albert Einstein to Alfred Hitchcock to Che Guevara. Supplemented with inked-in details such as facial hair and wrinkles, the skin-warping effect of tape stretched over cheeks and neck is astonishingly evocative while remaining utterly unconvincing: Akin to good caricature, the exaggeration of facial features makes Sugino’s versions of Einstein and Hitchcock and Guevara more readily identifiable than the subjects themselves. And yet caricature does not do justice to Sugino’s artistic accomplishment. Like many of the so-called outsider artists featured in an invigorating exhibition at Centrale for Contemporary Art in Brussels, Sugino upsets the comfort of categorization by following rules of his own making.

Part of a series of exhibitions displaying the extensive collection of Bruno Decharme, Photo Brut is focused on photography and photocollage by artists decidedly outside the mainstream. Most of the artists lack formal training, and some are mentally disabled, criteria that have frequently been used by the art establishment to select for special consideration work that would have been rejected based on establishment standards. These artists don’t require such backhanded validation. On the contrary, this work shows why the standards of the establishment are inadequate.

Photo Brut includes pieces by some of the most famous artistic outsiders of the 20th century, such as Henry Darger and Adolf Wölfli. In different countries and contexts, using a mix of media ranging from drawing to collage to writing, both constructed alternative realities so detailed that everyday existence seems impoverished by comparison. The authority of their fictions was enhanced with photography. Wölfli, for instance, appropriated photographic imagery from newspapers and advertisements to illustrate an epic 25,000-page biography, radically recontextualizing popular imagery to illustrate imagined episodes in a life lived outside the Swiss asylum to which he was confined for his whole adult life.

Because Wölfli’s artistic achievements were identified during his lifetime, his own biography is meticulously recorded, thus offering reasons to appreciate his art without diminishing the true value of his paintings as an original representation of his beliefs. Darger’s situation is slightly different because he created his ancient imaginary epics in secret while working as a janitor in Chicago.

Other artists in Photo Brut are shown with far less context, providing a very different kind of experience for the viewer. One of the most beguiling is entirely anonymous, known only by a collection of 950 Type 42 Polaroids found in New York in 2012. Dating from the 1960s, most all of the photographs are portraits of famous actresses. None were taken in person. Instead the artist photographed a TV screen. Was the artist creating a personal set of film stills? Was the subject of the pictures the character, the actress, or TV itself? Whatever the photographer’s intentions, we observe the act of watching, seeing one person’s view of popular entertainment unencumbered by biographical information. It’s an experience that could not plausibly have been provided by an artist in the mainstream working within the conventional gallery system that depends so heavily on personal branding.

There is a temptation to romanticize the foreigner, to see him as more original or purer than the professional with a well-established career. Photo Brut’s paintings demand a more nuanced response, one that does not pit outsiders against insiders, but that expands the definition of new art so that the difference disappears. The full richness of art depends on the equivalent coexistence of MFAs and janitors. The global is enriched through the other acts of biographical fictionalization of Adolf Wölfli and Lynn Hershman Leeson, or through other acts of self-transformation by Ichiwo Sugino and Cindy Sherman.

Including outside art in the museum is a smart start. The next step will be to integrate it with the rest of the barrel.

A community. Many voices. Create a free account to share your thoughts.

Our network aims to connect other people through open and thoughtful conversations. We need our readers to share their perspectives and exchange ideas and facts in one space.

In order to do so, please follow the posting rules in our site’s Terms of Service. We’ve summarized some of those key rules below. Simply put, keep it civil.

Your message will be rejected if we realize that it seems to contain:

User accounts will be blocked if we become aware that users are engaged in:

So how can you be a user?

Thank you for reading our Community Standards. Read the full list of publication regulations discovered in our site’s terms of use.