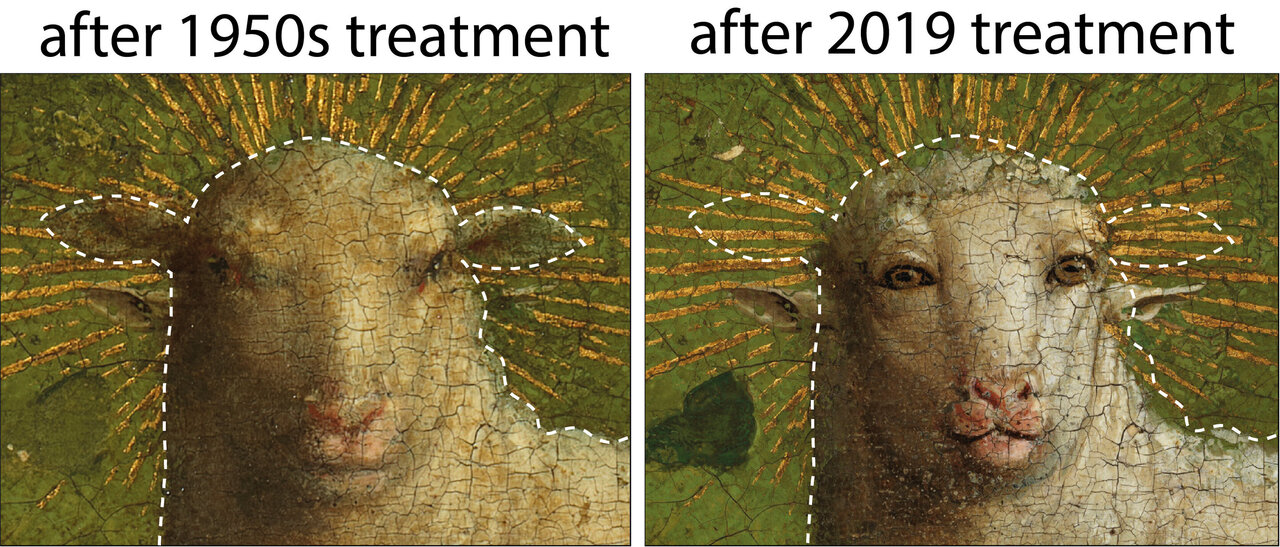

The ghent altarpiece is one of the founding masterpieces of Western European painting. The central panel, the Adoration of the Lamb, represents the sacrifice of Christ with a representation of the state of the Lamb of God on an altar, shedding blood on a chalice. During the conservation process and technical research in the 1950s, curators identified the presence of paint in the lamb and its surroundings. But on the basis of the evidence at the time, the resolution was taken to remove only the overpainting that obscured the bottom without delay surrounding the head. As a result, the ears of the Eyckian lamb were discovered, which caused the unexpected effect of a four-eared head.

During the recent central panel conservation remedy, the chemical symbols collected before the 16th century overpayment were removed, revealing facial features that predicted facets of the Eyckian lamb, at that time still hidden under the painting. For example, the smallest V-shaped nostrils of the Eyckian lamb are located above the 16th-century nose, as revealed in the mercury map, a detail related to the red vermilion pigment (Figure 2, red arrow). A pair of eyes looking forward, slightly lower than the 16th-century eyes, can be noticed in a hyperspectral infrared mirror symbol symbol in false colors (Figure 2, right). This symbol also shows dark preparatory lines that outline tight lips and, along with the presence of mercury in this area, recommend that the Eyckian lips be more prominent. In addition, the upper ears of the sixteenth century were painted on the golden rays of the halo (Figure 2, yellow rays). Gold is usually the artist’s definitive touch when performed in a painting, confirming the conclusion that the decrease in the ears is the original Eyckiano. Taken together, these facial features imply that, compared to the repainted face of the 16th-century restaurateur, the Eyckian lamb has a smaller face with a unique expression.

The new symbology also revealed in the past unrecognized revisions of the length and shape of the body of the lamb: a lamb more naturalistically with a slightly sunken back, a more rounded spine and a smaller tail. The artist’s sub-drawing lines used to draw the drawing of the smallest shape can be noticed in the hyperspectral infrared reflectance symbol in false colors (Figure 3, back left, white arrows). The mathematical processing of the reflectance dataset to highlight a spectral characteristic related to the white lead pigment gave a clearer picture of the smaller lamb (Figure 3, right back). The differences between handling fleece paint on the original small lamb and revised mastery of the larger lamb were also discovered in the second X-ray look and the surface of the paint under a microscope.

During the conservation remedy completed in 2019, decisions were reported through well-identified conservation strategies (high-resolution color photography, X-rays, infrared images, research of paint patterns), as well as new chemical images. In this way, the conservation remedy discovered the face of the Eyckian lamb, with eyes forward that meet with the gaze of the viewer. Only paintings that can be known as later additions dating back to the 16th century were consciously and safely removed. The Body of the Lamb, however, has not been replaced. Physical evidence indicates that the white lead paint layer used to define the second largest square rear was implemented before the recovery of the 16th century, but because research into providing cannot definitively identify whether it was a replacement through the original artist or artists. or a very early retrieval or amendment through some other artist, the extended definition of the Lamb has not been touched.