The recent government threats to TikTok raise questions about the future of the internet, which we once saw as free and democratic. Is that still the case?

Six women sent to prison because of their supposedly debaucherous TikTok videos in Egypt. The platform blocked entirely in India and maligned in the United States. TikTok, the video making and sharing app probably most known for its quirky video memes and gags made by people under 20, seems to be in many governments’ crosshairs. The attacks either come directly on the platform itself or to people using it in ways that violate the local social order.

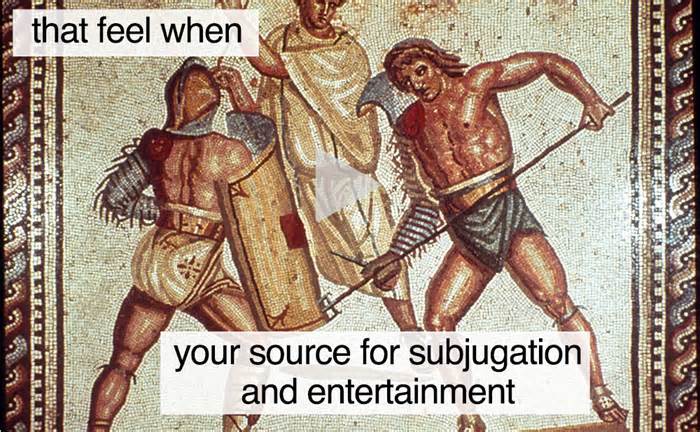

Public life and entertainment have long intersected with empire and control. In the first century AD, the Roman satirist Juvenal coined the phrase “bread and circuses” to describe the practice of leaders offering food and entertainment to distract the public from serious policy matters. The bread, in this case, was grain, and the circuses took the form of public games, like chariot races and gladiatorial combat, alongside other spectacles. The key here is that in written history, entertainment has often been a tool of state power. Those who challenged it, like the gladiator Spartacus who famously led a resistance against his captors, were punished severely.

The problem now, from a government’s perspective, is that the sites of our modern-day circuses are decentralized, as are our entertainers and rabblerousers. Any one account with enough followers and network savvy could quickly become a Uighur rights activist or Black Lives Matter organizer, and any one platform could enforce its privacy policies and algorithms inconsistently, silencing leaders or favoring disagreeable content. Herein lies the rub for an authority seeking to control online expression: how to provide the circuses while limiting the Spartacuses?

Blocking banal content on the internet is a self-defeating proposition. It teaches people how to become dissidents – they learn to find and use anonymous proxies, which happens to be a key first step in learning how to blog anonymously. Every time you force a government to block a web 2.0 site – cutting off people’s access to cute cats – you spend political capital. Our job as online advocates is to raise that cost of censorship as high as possible.

Despite efforts to place its US customers’ data on US and Singapore servers, TikTok struggles to shake the perception and reality that it’s a company owned and operated in a country that has historically exercised extraordinary powers over platforms within its borders; Microsoft, once the target of antitrust lawsuits and currently led by an immigrant, makes a comparatively more palatable owner to the current administration’s eyes.

Whether or not TikTok is blocked in the US or is ultimately purchased by Microsoft or another bidder or figures out some other solution for continuing to operate globally, one trend is clear: as physical borders close rapidly in the wake of COVID-19, digital borders are catching up. And like borders, arguments for safety and security are used to justify nationalism, capital and control. Verge journalist Sarah Jeong recently highlighted some of the oddities of calling out TikTok for its privacy violations, while seemingly ignoring a similar set of privacy concerns from Silicon Valley companies. Jeong called this practice “information-nationalism”: “When you play the game of information-nationalism, you don’t slander your enemies; you tell the truth about them, while hiding the truth about yourself.”

Scrivere Disegnando is an exhibition of more than 300 works produced by 93 artists whose subject is imaginary language.

Friend’s Email Address

Your Name

Your Email Address

Comments

Send Email